The Angel Fenstermacher

By Neil Plakcy

The night was alive with Jews. Everywhere Harris drove, it seemed that there were clusters of Jewish men on the street corners, walking home from Friday night services. It had been a cloudy, overcast day, unusual for Miami, and so it was a dark, velvety evening, full of the shine of street lamps and headlights, and the somber, dark-suited Jews.

These were not the Jews of his boyhood on Long Island in the forties and fifties, those prosperous burghers and matrons who supported their synagogues and dressed to impress at Friday night services. These were thin, bearded men, some young, some old, dressed uniformly in dark hats and dark suits, their white shirts glowing in the night.

It was not his kind of Judaism, he thought. His God believed in plaid sport coats, pocket handkerchiefs, and ladies in fur stoles. But then, he had not practiced his kind of Judaism for over twenty years, since his first marriage, when he had stood under the glossy white canopy and brought his left heel down hard on the glass. It was supposed to signify how frail the bond of marriage was, or so he remembered; and both his marriages had been the same, lasting as they did through some kind of inertia, a forward motion that had been jump-started at the wedding and then gradually dwindled until it expired like the last flame of a Sabbath candle.

He turned away from the populated area onto a side street and stopped at another light. He accepted that traveling around the neighborhood at the southern tip of Miami Beach was a slow process, as every light was extra long to allow the oldest and weakest a safe crossing. He was in no hurry; there was no one waiting at home for him, no supper in the oven, no welcoming hug at the door. He had all the time in the world.

The light turned green and Harris stepped on the gas. Suddenly, out of nowhere, an old man appeared in his headlights, another Orthodox Jew in dark suit and white shirt. Thin, frail, hunched over, he paid no attention to the flow of traffic. Harris slammed on the brakes, but it was too late. He felt a jolt as the car thumped into the old man.

Harris threw the car into park and jumped out. He picked up the old man’s upper body and felt how light he was. The old man’s eyes were flat and lifeless, and a thin trickle of blood rolled from his lip.

Harris knelt there in the glow of his headlights. The other cars and pedestrians seemed to have vanished. He looked around, trying to decide what to do.

Then he felt the man’s body become even lighter. There was a glow around him, a kind of white light similar to the way the shirts of the other Orthodox Jews had glowed in the darkness at other corners. The glow was oblong in shape and about three feet long. As he watched, it rose above his head, then to the level of the telephone wires and streetlights, and then higher still, until it blended into the cloud cover high above.

Harris was astounded. Had he witnessed the departure of a soul? He breathed deeply and looked down again.

His arms were empty. It was as if the man’s soul, in escaping, had taken the earthly body with it. Harris knelt there, bathed by his headlights, cradling air in his arms.

He shook his head. Had he dreamed everything? The man, the accident, the unearthly glow? He stood up and walked back to his car. Very slowly and carefully, like a man twice his age, he drove home.

Harris was a real estate speculator who bought buildings, fixed them up and resold them. He owned several properties in South Beach and had renovated an apartment in one of them for himself. Since his second divorce, his needs were simple. The apartment was Spartan, but a little messy. He walked inside and turned the light on, still uncertain about what had happened.

He went into the kitchen and looked for a candle. When he was young, he remembered his mother lighting thick white candles in glass jars on the anniversary of the death of loved ones. The glass was thick and wavy, embossed with Hebrew letters. His mother lit one for her grandfather, the Chaim for whom Harris had been named, and then later for his father’s parents and for her own. The dead were supposed to live on in the memories of those who remained, and their names were given to the next generation to further secure their remembrance. Harris had gone that far, naming his daughter Eve after his mother’s mother, an old woman in a babushka who lived in Brooklyn and who had taught him a few words of Yiddish when he was a child.

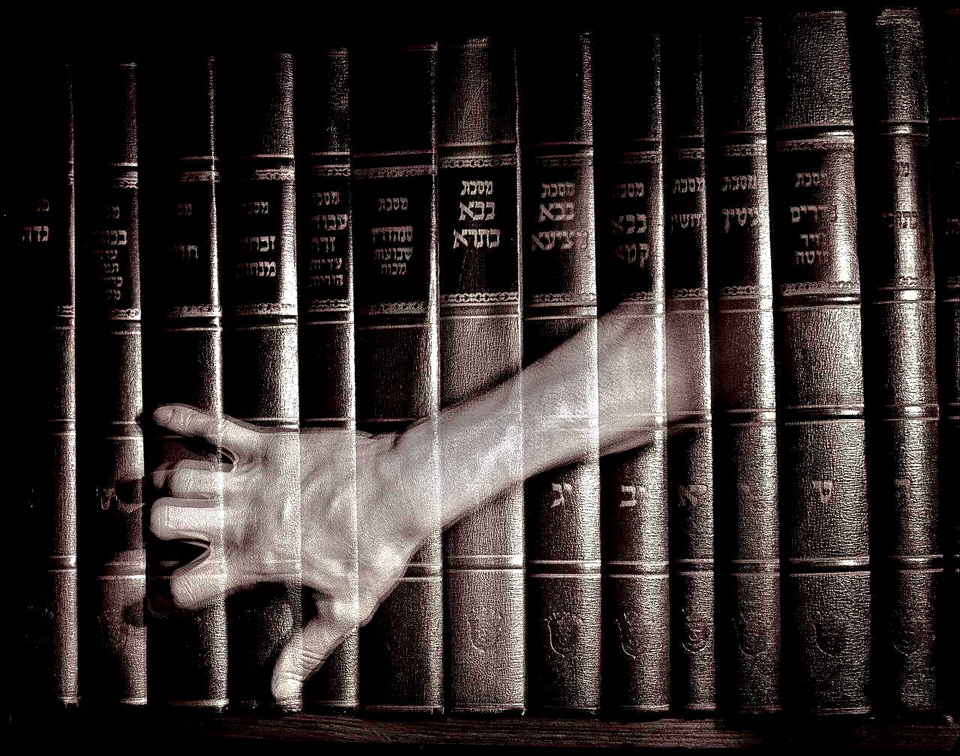

The closest he could find in his disordered kitchen was a squat votive candle left over from some long-ago party. Then, on a shelf in the living room, he found an old prayer book that had been his father’s. For some reason, Harris had kept it for all those years since his father died. He opened the book to the mourner’s Kaddish, the prayer that extols God’s greatness and was recited ritually by those who mourned.

He lit the candle and recited the prayer. For the rest of the evening, every time he saw the candle in the corner of the room, he thought of the old man and wondered what had really happened.

The next morning, Harris walked three blocks down the street to a small Orthodox synagogue he had often passed. A few dozen men there, most of them old, clustered in wooden pews in the filtered light from a pair of stained glass windows. The women sat behind a curtain, so that Harris could not see them, but the men all wore dark suits, white shirts and dark ties. They all either wore hats or yarmulkes. Harris looked a little out of place in his gray sports jacket and navy pants.

He sat at the back of the room, followed in the prayer book when he could, and stood to recite the mourner’s Kaddish at the appropriate time. Before he left he asked the rabbi how long he was required to observe the ritual period of mourning after a death.

“You are mourning your mother or father?”

Harris shook his head. “Then you have no obligation to say the Kaddish,” the rabbi said. He was a tall young bear of a man, with a thick curly beard and little ringlets of dark hair that dangled in front of his ears.

Harris thanked him and walked out into the bright sunshine. On his way home, he thought about the prayers that should be said after his own death. Neither of his ex-wives would mourn him, he thought; they might mourn the loss of their alimony checks, but not him.

Eve would not miss him either. They had never been close, and she had stuck to her mother’s side after the divorce. When she was seventeen, graduating from high school, he had called her at her mother’s house and offered to pay for her college education. She’d said, “I don’t need anything from you,” and hung up the phone. That was the last time they’d talked. Now all he knew was that she lived in New York, and worked, he thought, as a waitress.

Later in the day he went to a store on Washington Avenue that sold all kinds of Jewish items. He had often passed it, located between a kosher butcher and a Cuban fruit and vegetable stand, but he had never imagined he would go in there.

There were no other customers in the store, and even the proprietor had retreated to the back room. Harris felt out of place, but at the same time comforted. The small store was filled with fringed prayer shawls like the old men had worn in the synagogue he had gone to as a child, with menorahs like the shiny brass one his mother had treasured, a hand-me-down smuggled from Russia under someone’s voluminous skirts, and all the other accouterments of Judaism that were so familiar and yet so foreign to him. Familiar, because they represented his childhood, his past, but foreign because he had never made them a part of his own life.

On the far wall he spotted a display of Yahrzeit candles, like the ones he remembered his mother lighting. He had just picked one up when the owner came out of the back room and came up to him. “Yes, I remember you,” the owner said.

Harris turned to him. “But you’re the rabbi,” he said.

“We have a small congregation,” the rabbi said. “It is not a job I hold for money, but for love. Here is where I make my living. You are looking for a candle?” the rabbi asked.

“Yes,” Harris said. “My mother used to have one like this.”

“A very popular model.” The rabbi took the candle from Harris and carried it to the counter. “From Israel,” he said. He wrapped the glass with the candle inside it in heavy brown paper and put it into a white plastic bag with a blue menorah on it. The name of the shop was written in wavy characters that were meant to resemble Hebrew. “Will that be all?”

On impulse, Harris picked up a Jewish calendar. “And this,” he said.

Harris paid for the two things and picked up the bag, but he did not want to leave. “If you are not mourning your parents, then who? Your wife? No, God forbid, child?” the rabbi asked.

He didn’t know what to say. “A friend,” he finally stuttered. “A friend.” He looped the string of the bag in his hand and walked out.

That night, as dusk fell over the beach outside his window, he lit the Yahrzeit candle and said the Kaddish, even though the rabbi had told him he didn’t need to. The ritual made him feel warm, protected and safe. He sat in his big easy chair next to the window and watched the flickering light of the white candle, how it bounced and reflected against the glass. He thought of his mother, lighting those candles so faithfully, keeping the memory of her dead alive.

The next morning he returned to the synagogue, and after the service was over he walked to the beach. He sat alone on a shady bench near Ocean Drive and watched the sidewalk cafés opening. Waiters with ponytails and waitresses in very short skirts set tables, opened umbrellas, and pulled out menu chalkboards mounted on easels.

“It’s nice under here, in the shade,” a voice next to him said.

He turned. An old man sat next to him, where just a moment before there had been no one. When Harris looked closely at him, he realized the man was the same one he had hit with his car. “Who are you?” he asked.

“I am an angel,” the old man said. “My name is Fenstermacher.” He held out his hand.

Harris shook it. The man’s hand was thin and papery, almost weightless. “If you’re an angel, where are your wings?”

Fenstermacher waved his hand. “It’s not like you think,” he said. “Angels in white bathrobes with big wings, like butterflies. Artists. What do they know?”

“What do you want from me?”

Fenstermacher shrugged. “What have you got?”

“I’ve got money,” Harris said. “I own some property.”

Fenstermacher frowned. “What do I need with money?” he asked. “You think they have stores in heaven? Just imagine what the exchange rate would be.”

“I don’t understand,” Harris said. “Why me?”

Fenstermacher shifted uncomfortably on the bench. “You’ll have to forgive me,” he said. “I’m not very good at this.” He paused. “You shouldn’t give up on people so easily,” he said at last. “Your daughter, for example.”

“Eve? You know her?”

“Of course,” Fenstermacher said. “I may look a little lame, but I get around.” He leaned closer to Harris. “You ought to go to her. Make things up.”

Harris made a face. “I should make things up?” he asked. “Why me?”

“Always with the why,” Fenstermacher said. “You can’t take anything on faith? You can’t do it just because I tell you to?”

Harris sat back. There was a splinter in the wooden bench that poked him in the back. “She’s the one who hung up on me. She should be the one to make the first move.”

Fenstermacher pursed his lips. “You’re afraid?”

Harris shook his head. “Afraid? What of?”

“Maybe she doesn’t love you,” Fenstermacher said. “Maybe she’ll kick you out. I can see, you’re still human. You worry about these things.”

“Ever since she was twelve, she wouldn’t take anything from me. She used to mark my birthday cards, ‘Return to sender.’ How do you think that made me feel?” He looked toward the ocean.

Fenstermacher yawned. “I’m tired,” he said. “I’ll be going now. You think about what I said.”

“But wait,” Harris said. He turned back toward Fenstermacher, but the old man was gone. He got up and walked back to his apartment, muttering angrily at himself. Prepubescent fashion models and European tourists with backpacks gave him a wide berth.

He didn’t even have her number; he had to get it from directory assistance. After four rings, her machine clicked on. “Hi, this is Eve, I’m not here, you know what you’re supposed to do.” The machine beeped.

“Evie, this is your father. I just called…” He stopped. What was he supposed to say? “To see if you’re all right,” he continued. “Give me a call if you need anything.” He hung up and looked at the phone. “I hope you’re happy,” he said. “I tried.”

Harris went to services at the synagogue every morning for the rest of the week. On Friday morning, after services, he didn’t feel right. A week had passed and he should have been able to put the angel behind him. But he couldn’t.

Eve had not called. He thought about calling her again in New York but knew the results would be the same. Every time he went outside, he worried he would see the angel, that his performance would be judged. He refused to drive for fear that the old man would show up in his headlights again.

Finally he could not stand it any longer. He looked up Eve’s address in New York, called the airline and booked his flight. On his way out of the apartment he noticed the prayer book on the table by the door. On impulse he picked it up and tucked it into his carry-on bag.

Once settled in his seat, he couldn’t concentrate on the airline magazine, and only nibbled at the snack before him. He found the prayer book and opened it at random, to a section of passages from the Bible. He began to read about the rivalry between Jacob and Esau, and how Jacob stole the blessing that rightfully belonged to his brother. As the plane flew steadily northward, he read about Jacob’s sojourn in the land of Haran with Laban, and his marriages to Leah and Rachel.

He closed the book for a while to think about his own two marriages, and why they had not worked out. He considered himself rational, hard-working and stable. His ex-wives had said he was cold and unemotional, a workaholic who cared for little more than money. He had built and sold two businesses, and was now content to dabble with his investments, buy and sell buildings as he chose. Perhaps if he had been this relaxed when he was younger, he might still be married.

He went back to the Bible. Jacob fathered children like crazy, from Rachel and Leah and Bilhah and Zilpah, and finally had to leave Laban’s country and return to his own, fearing the wrath of his brother Esau. And then Harris sat up as if he’d received an electric shock. Genesis 32:2, “And Jacob went on his way, and the angels of God met him.” He read on, eagerly, voraciously, through Jacob’s battle with the angel, where the angel said, “‘Let me go, for the day breaketh.’ And Jacob said, ‘I will not let thee go, except thou bless me.’”

That’s what he should have done with the old man, Harris thought. He read on as Jacob received his blessing and his new name of Israel. He closed the book as the plane began its descent toward La Guardia. He should have wrestled the old man and exacted a blessing from him, instead of this silly errand.

He took a cab to Washington Heights, in the shadow of the George Washington bridge. Spanish music played in the street, and young men hung around cars with their hoods up. He walked down Fort Washington Avenue, looking at house numbers, until he found the building where Eve lived.

He was examining the buzzers when a short, heavyset Spanish woman came out and held the door open for him as she passed by. He nodded and thanked her, then walked up three flights to apartment 3G.

By the time he reached the door he was puffing for breath and his heart was racing. He had been spoiled by elevators, he thought. He rang the buzzer on the door and waited.

A few minutes later a woman’s voice said, “Who is it?”

He wasn’t sure if the voice was Eve’s. “Evie?” he asked.

“Who is it?” the voice demanded again. This time he was sure.

“It’s your father,” he said. “I’d like to talk to you.”

The door remained closed. “Go away,” Eve said.

“I’ve come all the way from Miami,” Harris said. “At least you can open the door and talk to me.”

There was silence behind the door. Harris wasn’t sure Eve was still standing there. He thought hard, searching for some sweet memory of Eve’s childhood that might make her open the door. “Do you remember that place across from the elementary school?” Harris asked. “The side of a hill. You and I used to go there to pick wildflowers for your mother. Remember?”

“What do you want?” Eve asked.

“I just want to talk to you,” Harris said. After a minute, he heard the chain sliding free and the bolts clicking. The door opened.

“I have to leave soon,” Eve said. She stood there in the doorway, blocking Harris’ view of the apartment. She looked strong and fierce, her dark blonde hair cut short, several earrings in each ear.

“May I come in?” Harris asked.

Grudgingly Eve stood back and Harris walked in. The apartment was tiny, just a studio with a Pullman kitchen and an unmade sofa bed. Clothes and toiletries were scattered everywhere. The paint on the walls was peeling and there was a large stain shaped like India on the ceiling.

“It’s good to see you,” Harris said.

“I wish I could say the same,” Eve said.

Harris looked around for a place to sit. There was only one chair, and it was covered with a pile of bras and t-shirts. He wanted to turn and walk out of the apartment, but he remembered Jacob’s battle with the angel. “I will not let thee go, except thou bless me,” he said to himself.

To Eve, he said, “You’re my daughter and I love you. Or at least I want to love you, if you’ll let me.”

“Why? Why are you here?” She stood with her hands on her hips, in a gesture Harris recognized was characteristic of her mother.

Harris hesitated for a moment. Should he tell her the truth? She’d never believe it. Her world was full of computers and mobile telephones and DVRs. Solid, rational things. How could he explain about the soul of a dead man rising out of his arms, up to heaven?

But he did. He picked up the pile of bras and t-shirts and put them on the side of the unmade bed. He sat down on the chair and she sat on the bed, and he leaned forward to her and described everything, from the old Jews in dark suits who were everywhere that night to the one who stepped in front of his car. “And then I looked down at my arms and they were empty,” Harris said. “I was kneeling there in the light of the headlights and I was holding my arms out as if there was a person in them but there wasn’t.”

“Cool,” Eve said. “But how did you get from there to here?”

He told her the rest of the story. “The old man said I should come and make up with you. I didn’t want to, you know. I’m just as stubborn as you are. You get it from me. But eventually I realized it was the right thing to do.”

And then, as he watched, Eve’s careful facade crumbled. Her chin started to twitch, and then her lip curled, and then tears began to trickle down her cheeks. Harris moved over to sit next to her on the bed, and he put his arm around her. She leaned into his shoulder and cried on his tweed jacket.

Eventually she sat up and dried her eyes. “I’m sorry,” she said. “But I’ve just been so unhappy. I hate the city. It’s dirty and disgusting. And everybody is so mean.”

“Why don’t you come down to Miami Beach with me?” Harris asked. “You can find a job, or go back to school, whatever you want. We could get to know each other again.”

Eve pursed her lips and then nodded. “I think it’s a good idea,” she said. “It shouldn’t take me long to pack.”

“Now?” Harris asked. “You can come now? Don’t you have to get out of your lease, shut off the phone, say goodbye to people?”

“I’m illegal here, so I can go any time I please,” Eve said. “I’ll say my goodbyes long distance.”

While she packed he called the airline and got two seats on the evening flight to Miami. By ten o’clock they were at his apartment. “It’s so beautiful,” Eve said as they got out of the taxi. “Can we take a little walk?”

“Sure,” Harris said. They dropped her bags in the living room and walked down to the beach. The sky was dark and clear and there were a few stars out over the ocean. They walked for blocks down the beach, until Harris finally said, “I’m tired. You go on, just pick me up here on your way back.”

“I’ll only go a few blocks farther,” Eve said. She strode off, looking serene and confident again.

Harris relaxed on the bench. “So, I was right?” a voice next to him said.

He knew without looking that it was Fenstermacher. “You were right,” Harris said. “So far. But will she be happy? Will she stay?”

Fenstermacher shrugged. “I’m an angel, not a fortune teller,” he said. “I can tell you one thing. You make your own happiness in this world, and the next one, too. People who want to be happy, they’re happy. Let me tell you, heaven has got its share of cranky people.” He shook his head. “Well, I’ll be going now,” he said. “Goodbye.”

“Wait,” Harris said. “Tell me more. Do you know my parents? How are they?” But the angel was gone.

Harris sat there for a while, not knowing what to do next. Then he saw Eve approaching. She was smiling and jingling a row of silver bangle bracelets on her arm. Harris got up to meet her, and felt strangely light on his feet, almost as if he had wings.