Remembering Zaha Hadid

Reflections by Alastair Gordon

Architect Zaha Hadid (1950-2016), who died in Miami in March, was a complex woman who made complex designs and introduced a sometimes baffling disregard for gravity and everyday conventions of Euclidean space.

In many ways, she was just starting to find her rhythm as a designer while simultaneously balancing her role as global design diva. I remember the 2014 groundbreaking for 1000 Museum Tower in downtown Miami. She entered the throng like a rock star and was quickly swarmed by fans who were trying to touch her or shoot selfies while crushing into her. She was smiling, but there was a vulnerable look of panic in her eyes.

Among other distinctions, she was the only woman to ever win the coveted Pritzker Prize outright, in 2004 (Kazuyo Sejima won with her husband/partner Ryue Nishizawa, in 2010). In doing so, she managed to penetrate the inner sanctum of a profession that has been dominated by men for hundreds of years. At the same time, she transcended gender politics and could stand as an equal to any architect, male or female.

To some, she could seem like an immoveable force, a rock—stalwart and stubborn. She staked out a critical position and stood by it throughout her 45-year career. This made some jealous and others oddly resentful. Zaha was an inspiration for younger designers who looked up to her as a role model. (Based in London, she had launched an architectural practice in the 1970s with only four employees, but it grew to more than 400.)

Her friends saw a sweet innocence beneath the sometimes intimidating facade.

“For Zaha, it was always about space, not so much about form as pushing the experience of space,” said Claudia Busch, a Miami-based friend and former associate.

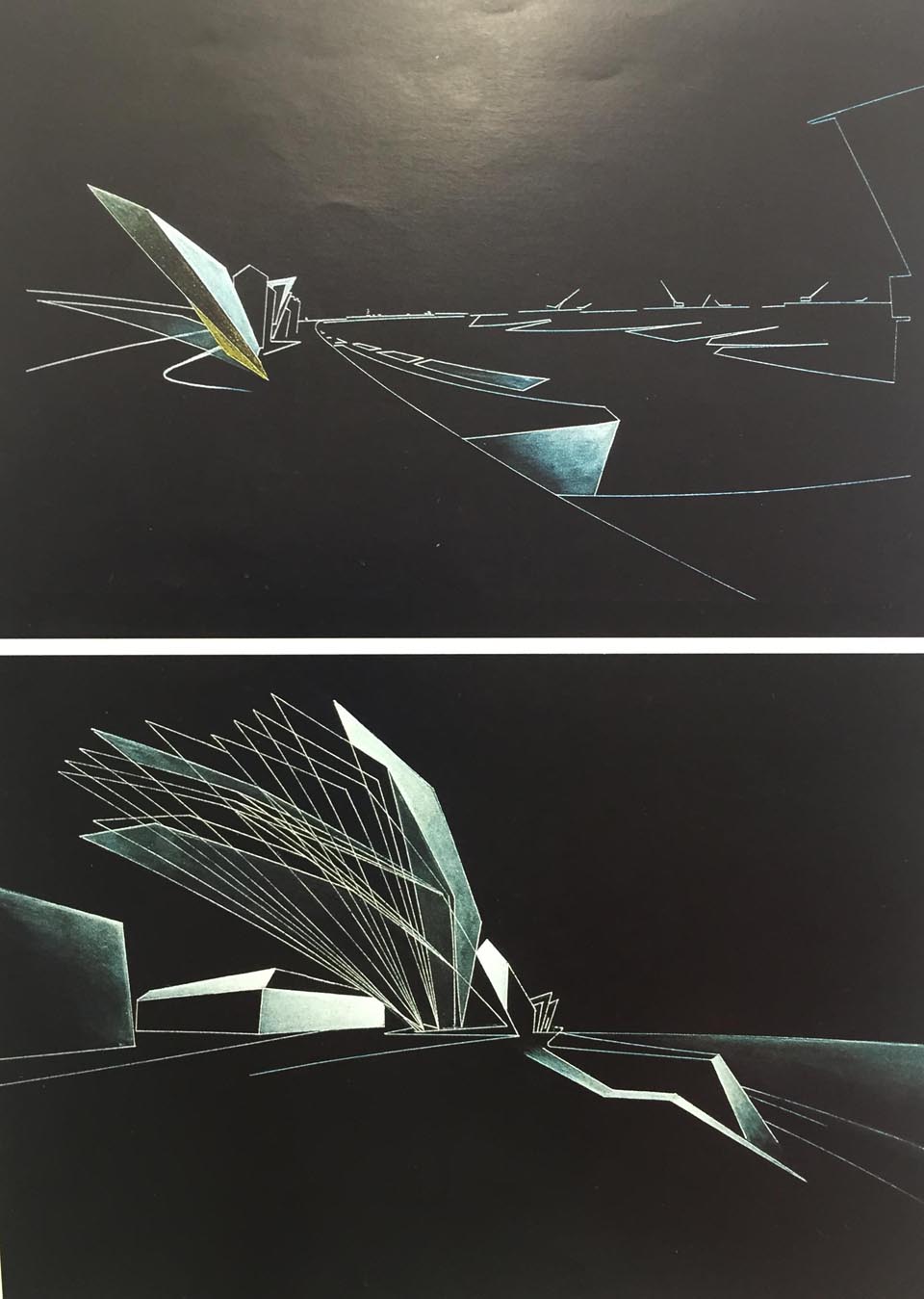

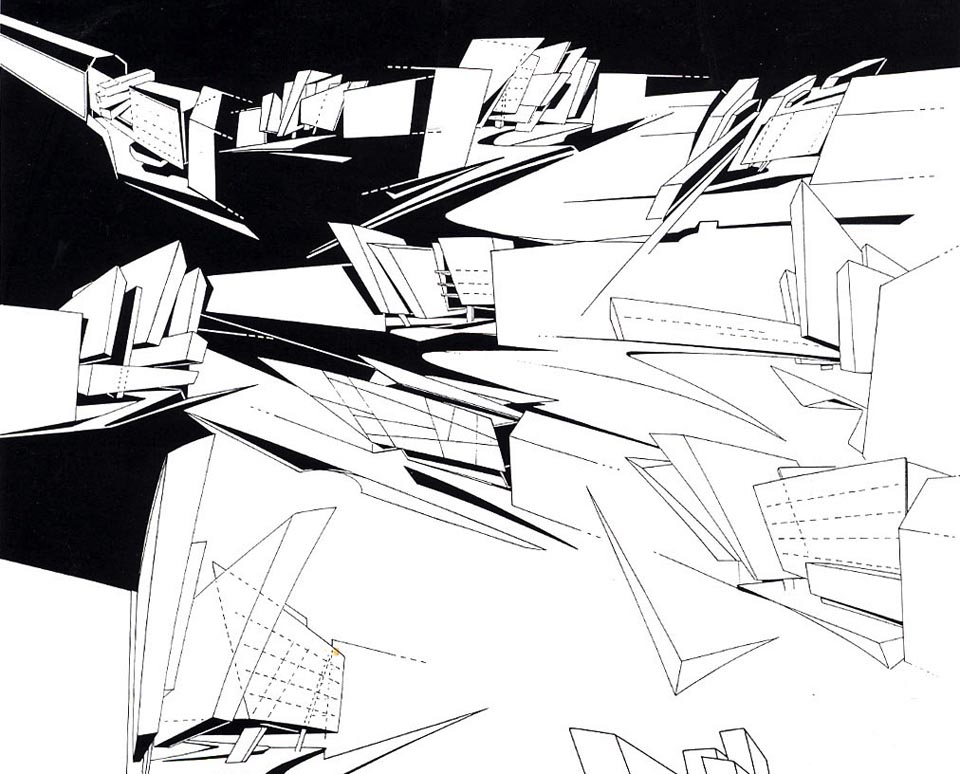

Some of the shock over her sudden death at age 65 may come from the fact that she was still in the middle of a brilliant career, and there was so much more to come. I will never forget seeing her early drawings in the Deconstruction exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1988. The imagery was at once seductive and slightly terrifying: a universe of colliding forms, shifting planes and tortured projections that pushed the orthogonal beyond recognition. These early manifestations still look fresh and subversive today.

Her presentation for a project in Hong Kong featured cascading wedges, scattered bands of color and overlapping geometries that might have been turbulent urban eruptions out of some dream world. It was certainly art, but was it architecture, and how would it ever get built? (It would not.)

One cannot underestimate the effect those renderings had on a generation of architects and designers. While surfing the cusp of a brand new digital frontier, the work also acknowledged the fractured legacies of Russian Constructivism, in particular the work of El Lissitzky, Kazimir Malevich, Varvara Stepanova, and Aleksander Rodchenko.

The building part came relatively late, her first being the Vitra Fire Station in Weil am Rhein, Germany, finished in 1993 with its monolithic walls and outrageous cantilevers, reaching and tilting as if seen through a distorting lens, but somehow containing an operational firehouse. “I don’t want to see a building,” she said to her design team. “I want to see a landscape.” She was 43 at the time; architects often start late and don’t mature until their 50s or even 60s.

At some point in the 1990s, her sharply angled and wildly cantilevered forms gave way to a more fluid, ribbon-like vocabulary that featured elastic wall planes, seamless transitions, sweeping ovoids, and hyper-extended rooflines. Consider the looping, mobius roof at the Heydar Aliyev Center in Baku, Azerbaijan; or the gravity-defying pods for the Messner Mountain Museum perched high on Mount Kronplatz in South Tyrol, Italy. Her Phaeno Science Center in Wolfsburg, Germany, hovered above its site like an alien starship.

“It took us months just to understand the shape,” said the engineer of one of her more daring structures. Certain forms were impossible to delete from one’s mental screen, such as the undulating shape of the Aquatics Centre at the 2012 Olympics in London, or the MAXXI Museum (2010) in Italy, with its multi-tiered roof that echoed the strung-out forms of overlapping highways while challenging the historic patterns of Rome itself. (Some still insist on seeing her design for the Al Wakrah 2022 World Cup Stadium in Qatar as a 40,000-seat vagina.)

There were also smaller installations and temporary pavilions that demonstrated her full range as a sculptor-architect, unimpeded as they were by functional necessities: the Chanel Mobile Art Pavilion which opened in Hong Kong, Tokyo, New York, Paris; the cocoon-like Burnham Pavilion in Chicago; the spectacular Bergisel ski jump and Nordpark Railway Stations, both in Innsbruck, Austria. On a smaller scale, she designed furniture and jewelry with as much passion and intensity as she put into her full-scale buildings.

Even when the first buildings were completed, there were doubts and speculation. Some critics dismissed her visions as indulgent and self-aggrandizing, but in that way she was joining excellent company: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim in New York, Jørn Utzon’s opera house in Sydney, and Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim in Bilbao were all deemed unbuildable and grossly over budget in their time.

But those same buildings redefined the identity of their respective cities, just as Zaha’s best work captured the sense of displacement and fluctuating time warp that author Pico Iyer refers to as the Global Soul. Zaha moved around the world like a bird in constant motion — from London to New York to Korea to Italy to Qatar — occasionally setting down and relaxing in Miami, a city that she grew to love.

She first came to Miami Beach about 16 years ago and stayed at the Delano, then the Raleigh, the Setai and finally moved into the W — where she bought an apartment that she redesigned to her liking. From her perch on the Beach she could look across the city that she came to embrace as her second home.

“Zaha loved Miami. It was her home. She found so much solace here,” said Sam Robin, designer and close friend. “She was always an inspiration in her art and architecture and especially in her personal friendships.”

She loved fashion, and when she walked into a room, people stopped and took notice. The clothes she wore often resembled her most flamboyant buildings. Only a few nights before her unexpected death, she emerged from an upper balcony at the Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts decked out in a remarkable dress by her favorite designer, Junya Watanabe, that was sculpted like a geodesic pattern in shiny black plastic.

Over the years she has left her own imprint on Miami. Zaha showed drawings at Art Basel Miami Beach and exhibited her biomorphic furniture at Design Miami.

“She was amazing,” said Craig Robins, founder of the design fair and a close friend. Zaha designed Elastika, a permanent installation for the launch of Design Miami in 2005, with white cartilaginous forms that stretched between the balconies of the Design District’s historic Moore Building. More recently, she designed a bathroom in Robins’ own house, a white womb made from Corian with a single unbroken surface that morphs around the space, absorbing bathtub, shower, cabinets and sinks, and turning a mere bathroom into a time-travel device.

“She loved the laid-back tropical feeling of Miami,” recalled Robins. “She also liked the fact that it was a growing, vital city.”

Zaha evoked that same vitality in her proposal for a Miami Beach parking garage near Collins Park that took the form of a layered, swirling suspension of matter. Her 1000 Museum Tower condominium building, with its bone-like superstructure, is still under construction in downtown Miami. When the 62-story building is finished, it will not only change the skyline but the identity of the city itself and serve as a fitting memorial for such a remarkable woman.

Zaha was a protean, creative force of nature. There will not be another like her for a long time.

[Editors Note: A version of this article by Alastair Gordon first appeared in the Miami Herald on April 1, 2016]

Reflections by Claudia Busch

It was in Hamburg during the winter of 1989 on a rainy, cold evening that I walked into a private exhibition opening reception for paintings by Zaha Hadid. The gallery was in an old apartment building of the 1920s with high stucco ceilings. A series of large, colorful paintings were displayed on white walls. I was one of a few local students who had the opportunity to see her work in the exhibition. One of my favorite paintings was of a slender office building in Berlin. The sky was painted red. Who would paint a sky red? The architecture was dynamic and energized, defying gravity. The spaces were fluent and coherent with a consistent movement.

At that time Zaha had already won the Peak Competition and was a celebrity within architecture circles. I had studied her work through a GA book that I found at the architecture bookstore in Hamburg. It was in stark contrast to the rigid German architecture education I was receiving. For me, Zaha’s work was full of life and exceptionally different from how one would experience space. I wanted to work for her. I was lucky. I got hired.

Zaha’s London office was small, filled with dedicated and talented people. It was a strong team, and Zaha was leading us into new territories. She was tough, but incredibly charismatic. She had clear ideas that she conveyed to the team to explore. Similar to a studio environment, several people were given different tasks and created a catalog of ideas for one project. All the drawings, paintings and models appeared in weekly beautiful presentations like magic.

The mode of representation was an important factor in how the design was generated. Zaha always asked for perspectives such as the project seen from a flying airplane, moving around, moving through, on top or from the bottom. One of the exceptional drawings captured a building as one would move around and see all views simultaneously. These rotating perspectives are similar to the photographs by Etienne-Jules Marey, which record several phases of movement in one image. At the time, all drawings were done by hand with incredibly sophisticated technical skills. But they already had the precision and complexity that we see today using digital tools. She anticipated that the representation of space would change and so, too, the making of space.

I remember working on a study model for Vitra Fire Station led by Patrick Schumacher. Zaha talked to the team about treating the whole site as a landscape and investigating the site beyond its boundaries. It was the first time for me not seeing the building as an object. The studio explored how to integrate and connect the building into the site and how the site would affect the building. Often her work is classified as iconic. But it was her study of the urban context, the idea of continuity of space, and the body moving and experiencing space that changed the form of architecture.

Zaha impacted my life in many ways: she was a mentor, architect, close friend and an exceptional woman. My career had just started, but I knew she would change architecture. Over the last decades, drawings became reality. I now visit her buildings and experience the dynamic fluent spaces that I first saw as paintings in an exhibition space in Hamburg.