The Accidental Dönmeh

Editor’s note: In 2016, Alfredo Garcia submitted a story to ArtSpeak about Jonatas Chimen, a Brazilian-born and raised artist, who moved to Miami at the age of 16. Though Chimen was Catholic, he was soon being asked if he was Jewish. That question, and the elusive response of his family, launched Chimen on a ten year journey, culminating in the knowledge that his family was forced to convert from Judaism to Catholicism in 1492 during the Spanish Inquisition. Chimen gathered all of the paperwork he had amassed tracing his roots and incorporated the documentation into his artwork.

When we published the Jonatas Chimen story in ArtSpeak, I sent links to the story to an international database of friends of ArtSpeak. To make a long story shorter, an art curator in Israel contacted me and told me about C.M. “Memo” Kosemen, an artist with a history similar to Jonatas Chimen, except that his family was forced to convert from Judaism to Islam in the 17th century in Turkey. Perhaps it shouldn’t be a great surprise that the artwork of Kosemen and Chimen have a similar feel.

It all started with a breakup.

Back in 2011, C. M. “Memo” Kosemen, had reached the end of a passionate — yet tortuous — relationship. For many reasons, Memo felt that the relationship had to end, but this did not make the decision any easier. “I had to leave her,” he said, “but I regretted this for a long time. I felt really guilty, like I had dropped a bomb on her life.”

As many of us do, Memo found himself turning to his professional and artistic work to alleviate his suffering. He was, however, also taking many walks to clear his mind — one of which led him to a special cemetery.

The cemetery that Memo visited was different than the others he had seen in the city of Istanbul. In addition to etchings of the deceased’s name, birth and death years, each tombstone bore an image of the deceased — stoic, powerful, and pristine portraits, framed in ovals and protected by glass.

Overwhelmed by the images, Memo began taking photographs of the portraits. During his lengthy walks, dripping with guilt and remorse from his recent romantic breakup, Memo would set up his tripod and take meticulous photos of the portrait on each tombstone. Over time he realized that each portrait bore the signature of the same person — Osman Hasan — yet Hasan was an ephemeral character. Memo also noticed that the portraits were quite fragile and subject to vandalism. “I was motivated when I saw that some of the portraits were smashed by hooligans during a revolt,” he said. “They just smashed them for fun while they were hiding in the cemetery.”

Over time, Memo began thinking about using his photographs to make a book that would document the existence of the men and women portrayed on the tombstones. “I started to see this as a tikkun,” he said. “The book must be made and I was the only person who could do it. And then there was Osman Hasan. Nobody had written about him. Either I write about him, or nobody will,” Memo thought.

“By making a book, I really felt like I was saving people’s lives, which is the greatest honor one could hope for. I could save their memory, a memory that is being threatened by the rise of nationalism and malignant identity.”

It is important to note that Memo described his efforts as tikkun. This word comes from the Jewish tikkun olam: the responsibility that all Jews have to repair the world for the better. Instead of focusing only on the health, welfare, and wellbeing of oneself, tikun olam encourages Jews to take charge of caring for society at large.

But why did Memo, a secular Turkish citizen, embrace the concept of tikkun? Memo’s artwork — often filled with strange animals or ethereal human shapes — does not give the impression that Memo is Jewish. And Memo does not engage in practicing Judaism.

Memo did, however, discover that the men and women in the cemetery were Dönmehs — Jews who chose to convert to Islam in order to avoid persecution in 17th-century Spain. While outwardly Muslim, the Dönmehs were Crypto-Jews who practiced their Jewish faith in secret. And Memo was of Dönmeh descent. “I am an ethnically Jewish, secular Turkish citizen,” he states. “That’s what I call myself. It is a nice calling card.”

Although Memo had always known of his Dönmeh lineage, it was not until the book was published that Memo began “delving deeper” into the connection between his artwork and his Dönmeh identity. He was invited to conferences on Jewish studies, for instance, and Crytpo-Jewish events. Few Dönmehs remain in the world, and few know the history of this group. As a result, Memo was invited as “a kind of honorary representative from the other side of the world.” And although he always stressed that he was not a society elder or a person of status among the community, listeners and viewers continually saw him as an ambassador of the Dönmehs.

The book, in short, launched Memo into the role of accidental Dönmeh — a worldwide representative of a community he barely knows.

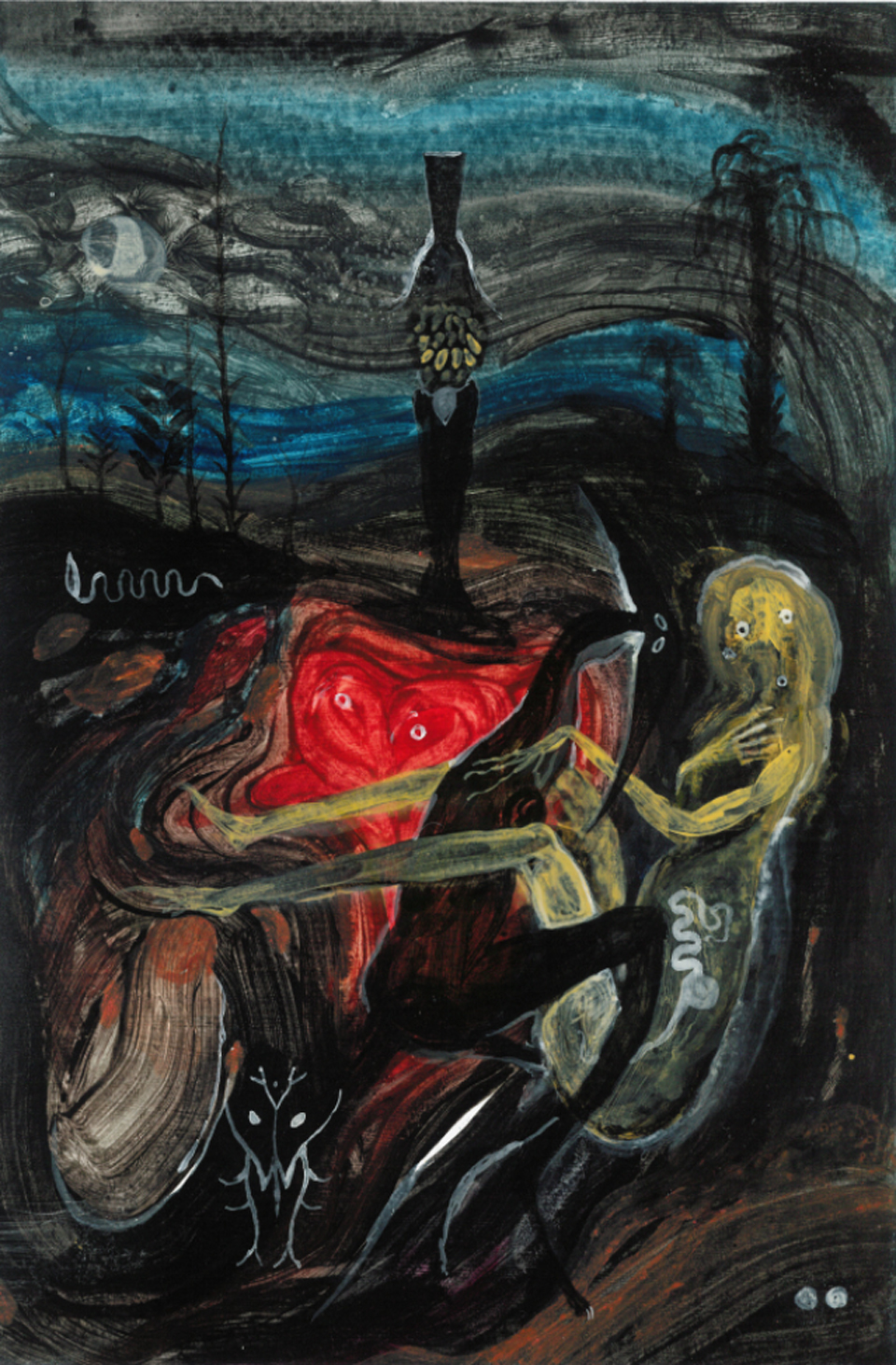

Attending conferences, addressing audiences of Dönmehs and those eager to learn more, and traveling the world meeting Crypto-Jews, caused Memo to reconsider his own art. Viewers from around the world alerted Memo that his paintings were full of Jewish imagery and symbolism. Serpents, trees, beings with horns, dark images, females — there were a variety of elements that, unbeknownst to Memo, overlapped with Jewish mythology. “I did not notice the connections,” Memo said. “But I did my research and noticed coincidences that didn’t seem like coincidences.”

As a former paleontology illustrator, Memo includes elements of his scientific studies of animals into his artwork. His paintings often present a kind of “enchanted garden of symbolism and primeval mythology,” as he states. But more and more, Memo also sneaks in Dönmeh or Jewish symbols in his work.

The painting titled ”I am Adonai,” for instance, is a product of the melding of his scientific and metaphysical selves — a snake god raising its arms in triumph, hands clutching serpents, and two other-worldly characters watching this whole spectacle amidst a completely surreal realm. “I think this piece is about the desire to break out that people in Turkey feel — at least I feel. I just really want to tear out and scream at people — if you only knew what you are missing! A plea for the ignorant, for the veiled.” Viewers may not immediately see the link between these animal figures and the title of the piece, but Memo chose the title to incorporate his Jewish roots.

With his book of the cemetery portraits now published, Memo’s connection to his Dönmeh roots and Jewish past show up in subtle hints in his paintings. The book, however, has changed his life. Now a member of a worldwide Dönmeh community, Memo sees his tikkun as integral in the creation of new friendships and connections. He remains, in short, the accidental Dönmeh that has been warmly received.