From the Spanish Inquisition to Miami:

The Art & Journey of Jonatas Chimen

Themes of identity are often an integral part of artwork and aesthetic production. But it’s probably not the case that the expositions on identity span six centuries and five countries.

“At 16, I came to the U.S. from Brazil,” Jonatas Chimen told me as we chatted in his studio/apartment, “and people started asking me if I was a Jew.”

These questions were strange for Chimen (why would somebody ask him if he was a Jew?), yet they were also incredibly relevant. For as long as he can remember, Chimen told me, there was a mixture of rites, rituals, sayings, and practices that he and his family observed that seemed at odds with other customs in his surrounding community in Brazil.

“Do not point to the stars on Friday nights,” he was told, because your fingers will fall off. Another popular saying was “Do not cry for the bull.” And as his elders emphasized: always, always, always marry within the community—even if this means marrying a first cousin.

Upon arriving in Miami in 1998, Chimen took the first steps toward understanding his background, a process that created “a great revolt in myself,” as he said. Chimen was indeed a Jew. But he was not just any Jew. Chimen was the descendent of Spanish and Portuguese Crypto-Jews: an exiled community that survived forceful conversions to Catholicism and threats of execution during the Spanish Inquisition. “It was like finding out that I was a part of some ancient civilization.”

Although it is far from a homogeneous and monolithic group, there are certain traits that distinguish Crypto-Jews worldwide. As the current generation of a lineage that goes back to the massive expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492 and their subsequent persecution in Western Europe, Crypto-Jews often continue the traditions and practices of their ancestors who feared for their lives. As a result, these men and women have outward displays of Christianity—going to mass, making the sign of the cross—while enacting Jewish practices in private, such as pouring wine and blessing it with the Kiddush prayer on Friday evenings.

For Chimen, his first years in Miami marked the beginning of a painful and long process of learning about his Jewish roots and understanding an entire world of identity amidst forced conversion and ambiguity. Not pointing to the stars on a Friday night? That was because one could be killed for doing that in 16th century Spain: pointing to the stars was an indication of the oncoming Sabbath and could have outed one as a Jew. Not crying for the bull? This was a sad saying of loss for Jews. In using the feminine form of bull in Spanish, Crypto-Jews were instructed to not cry for “la tora,” a clear homonym for Torah, the sacred text of Judaism. And marrying within the community? This was a clear mandate to maintain the Jewish lineage at all costs.

In many ways, Chimen’s works are the artistic expressions of a painful decade of searching, discovering, reading, and realizing his identity. There were searches in databases and archives worldwide, both digital and in print. There were classes in Hebrew and “Landino,” a kind of Judeo-Spanish that distinguished Crypto-Jews. And there was the constant petitioning of rabbis worldwide to recognize his real Jewishness.

Amidst all of this, however, Chimen was producing art. And it is with a careful eye to Chimen’s past that we begin to see the real battles over identity play out in his artwork.

* * *

“Here, let me pull them out and we can take a look at them in detail.” Chimen’s apartment is tucked away on the third floor of a classic Miami Beach apartment building: the kind with bright exterior paint, old windows, and terrible parking. Although his living room and bedroom double as one of his studios, the place is surprisingly clean. Just a few dashes of colors and stains on the wall show that an artist works there.

Chimen rushed into his bedroom and walked out with a pile of hastily stacked and relatively disorganized paintings and collages made on wood boards. He carried them into the living room and began placing them wherever he could find a space—we moved flowers, coffee table books, and magazines just to make room.

“I know that it doesn’t look like it, based on how unfinished and disorganized they all are, but this is my most important collection.”

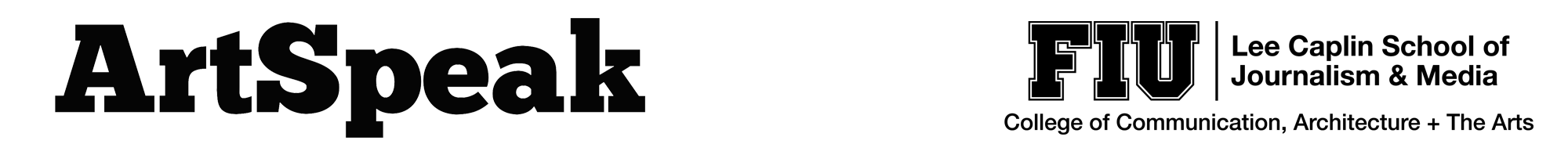

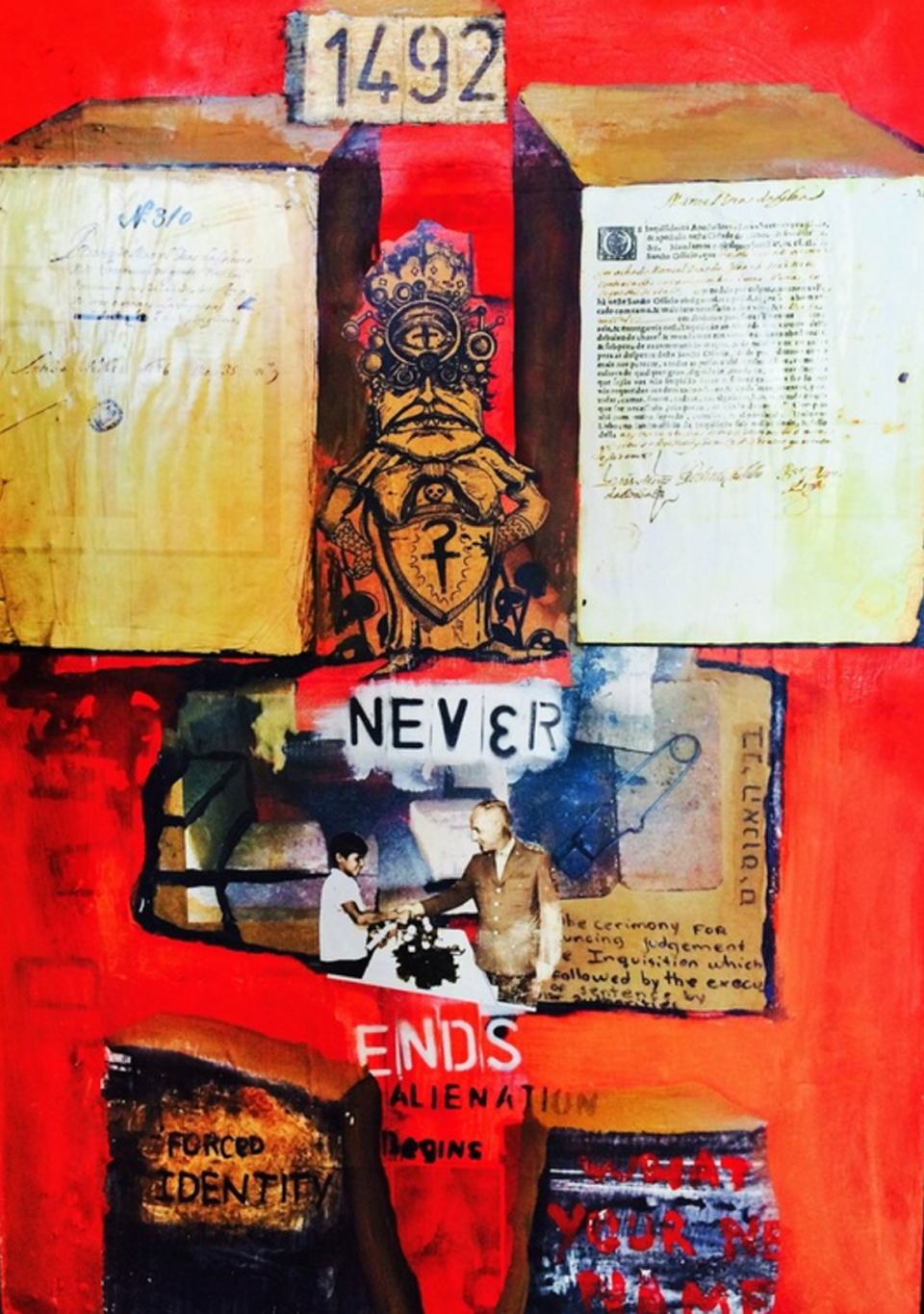

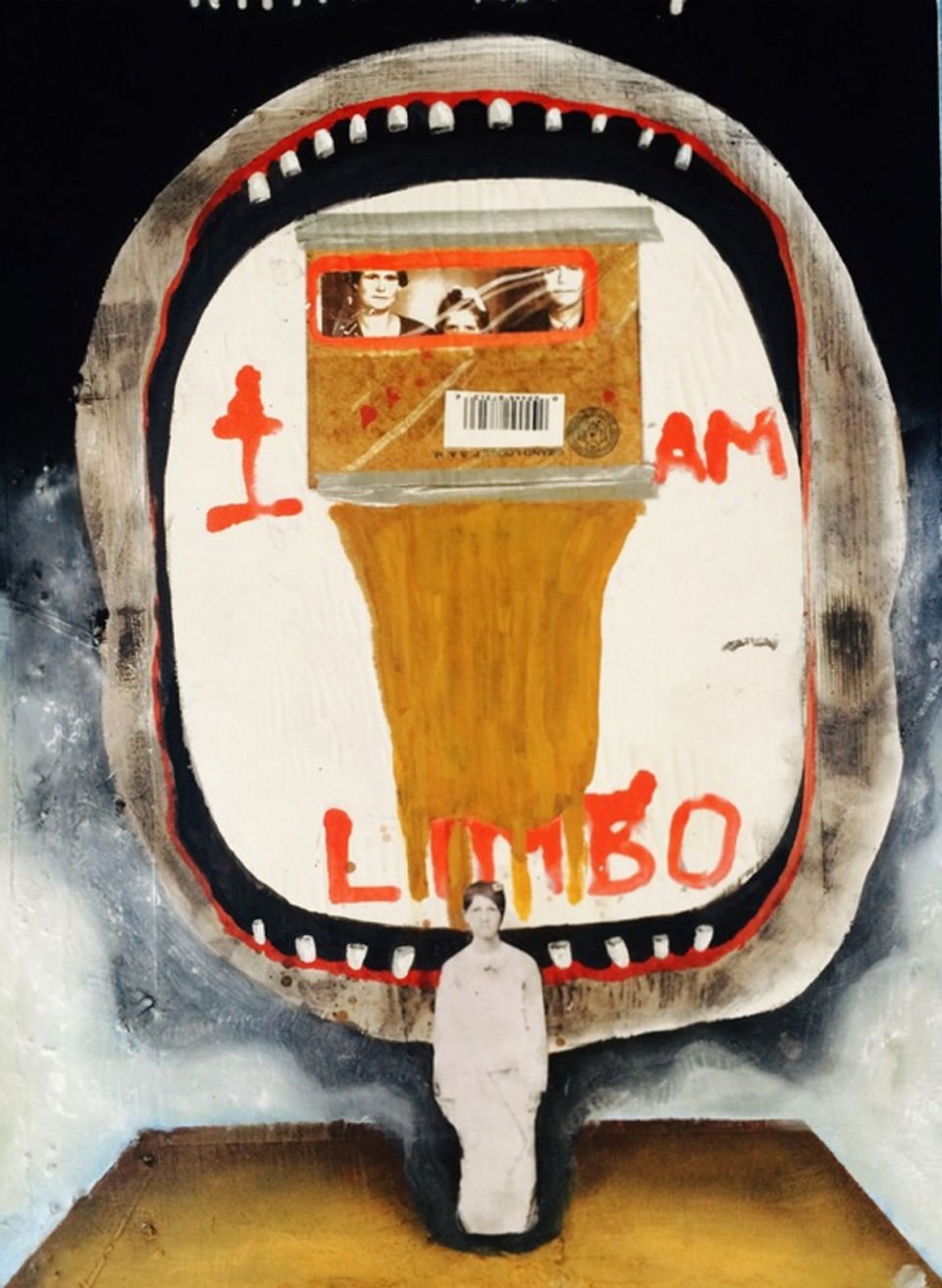

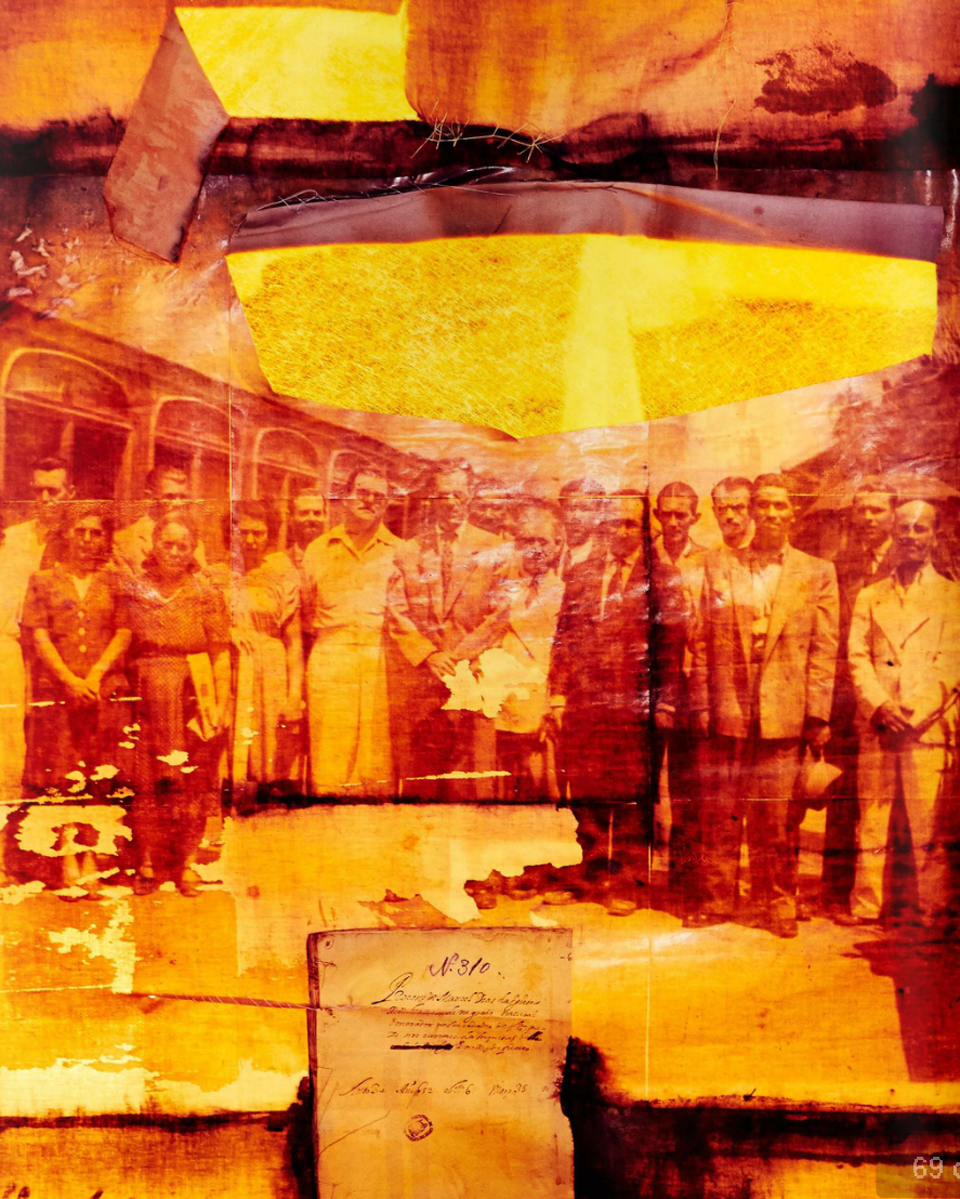

This was Chimen’s Diaspora Creature collection, a series of 20 assemblages on wood panels. With layer upon layer of text, paint, printouts, and stenciling, these pieces present the excruciating journey that Chimen took over the course of 10 years. In the process of uncovering his Jewish roots, Chimen collected documents, photos, archives, and even a DNA analysis that added to his understanding layer upon layer, one element at a time.

The images are often disturbing and difficult to digest. Monsters appear on some panels flanked by silent and soft images of ancestors. A gaping whale’s mouth fills another panel ready to swallow an image of a past relative. “What am I,” spans the top of the whale piece. “I am limbo,” it says within the mouth.

As with Chimen’s other works, the Diaspora Creature collection is an intimate expression of his path to realization. Once he decided that he would reclaim his Jewish identity, Chimen realized that it would not be easy to convince others of his roots. As in many religious communities, the recognition of membership requires a series of documents that assert a person’s lineage and rites of passage.

For most, this means asking parents and/or grandparents for marriage certificates or letters from religious leaders. But for Crypto-Jews, the retrieval of documents and lineages can be a series of Herculean tasks. What if, for instance, the most recent document that you can get a hold of is a letter from the 15th century? What if these documents require intense translation? What if the only thing that you have is your Jewish practices—many of which have confusing and confounding connections with Christianity?

Eventually, Chimen was able to put together all of the documents that were required in order to present to an Orthodox rabbinical court, a kind of ultimate arbiter of Jewishness worldwide. Many had encouraged Chimen to just convert to Judaism and be done with it all. But having come from a long lineage of oppression and alienation that was instigated by conversion—the forceful conversion of Jews to Catholicism in 15th-century Spain—Chimen refused this easy path.

“I encountered documents of family who had died for being a Jew,” he said. “So no: conversion was not an option.”

After years of excruciating work, Chimen finally received what he was looking for: a certificate of return. That document was full proof of Chimen’s Jewish identity that could be accepted worldwide. With ancestors starting in Spain and moving to Portugal, descendants continuing on to Amsterdam before moving to Brazil, and then finally his own family uprooting to Miami before he began inquiring about documents and peoples from as far away as Israel and South Africa, Chimen had finally reached the full recognition of the identity that he had come to realize was his own.

It took 10 years, he emphasized, but now it’s all done. And throughout it all, Chimen was making art.

* * *

As with many of his other pieces, Chimen’s Diaspora Creature is a collection that is variably displayed depending on the emphasis of the presentation. These panels in particular were at first thrown on the ground and viewers were encouraged to walk all over them. Small exposed nails on the wood panels cause the public to feel a bit of the torture that Chimen went through in his process of identity formation. The composite of words and pictures followed this evocation with indications of struggle. “Hybrid.” “Survive.” “Alien.” “Reprogram.” There is no question that these are works of painful liberation.

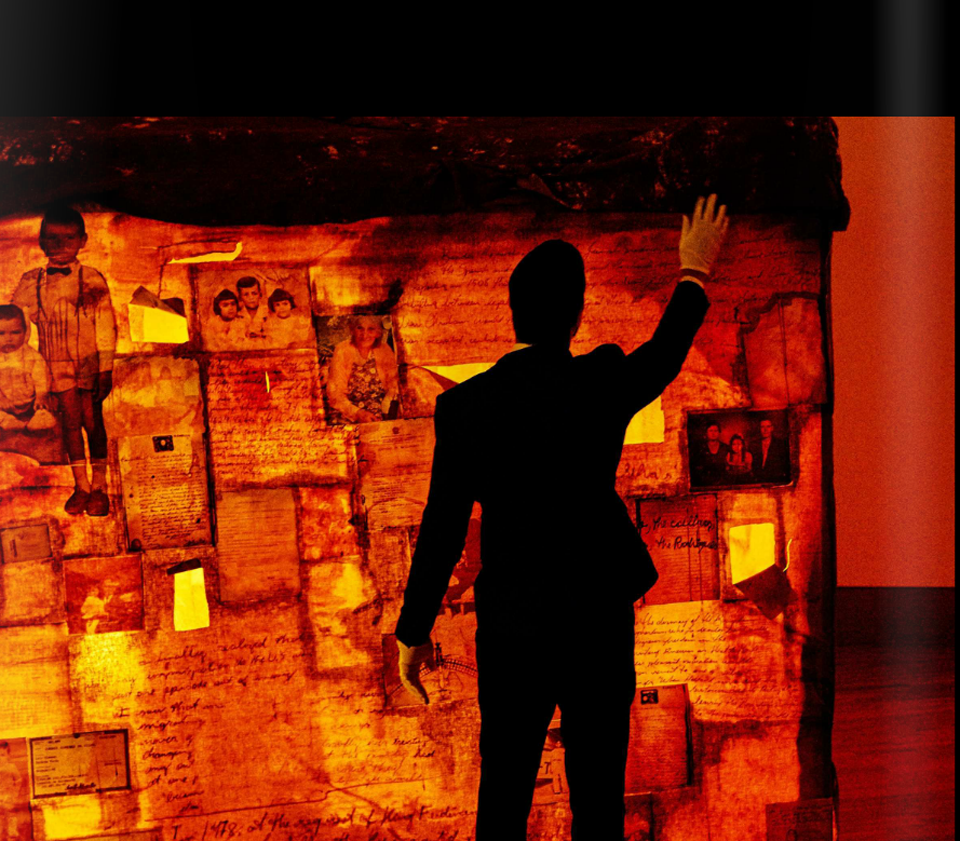

Having collected thousands of documents and pictures, Chimen also produced the large, multi-sensory project titled “In Thy Tent I Dwell,” a literal tent built through sewing together birth certificates, inquisitional archives, immigration documents, and other forms and images. Spanning 10 feet by 10 feet, this large tent fully immersed viewers into the cascade of words, emotions, and existences of the ancestors that preserved a culture amidst persecution.

None of these men and women survived to see Chimen finish the circle back to the beginning, but they are all present in that space, confirming and sanctioning his grand return.

In Thy Tent I Dwell was first exhibited at the Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum in the Spring of 2016, and then at the Jewish Museum of Florida in the Summer of 2016. The piece is schedule for exhibition in Hamburg, Germany in 2017. Chimen earned an MFA from FIU in 2016.

With emphases on diaspora, exile, discovery, and identity, Chimen’s work appeals to viewers both within and without the world of Judaism. In Miami, the most obvious connection lies with Cuban refugees and the families that have grown up amidst an exile that is only just beginning to change. But with larger shifts in world politics and markets, there are also others in the city who identify with these feelings of estrangement. Whether due to poverty, regime changes, or threats to their lives, Miami is full of men and women who arrived in the United States and live in perpetual displacement.

Chimen is not the only one in Miami who has taken a journey to discover a piece of himself by digging into his past. But lucky for those of us who are still in the process, we have Chimen’s artwork to help guide us.